Using Intelexual Media primers, you can get all the information you need on a complex subject in thirty minutes to an hour! This primer contains three videos and a list of resources for your learning pleasure!

I was a sophomore at The Ohio State University during the early days of my feminist enlightenment. Almost overnight I went from being the girl who chuckled at the notion of rape culture in my women’s studies classes to being one of those “annoying feminist” always angry on the twitter timeline. One person who took notice was a friend of a friend named Brooke. “Lexi’s a baby feminist, its so cute.” she tweeted. I was offended, especially since Brooke was an intelligent future lawyer whose tweets I admired. I believed in the social, political, and economic equality of the sexes! Wasn’t that enough to be a feminist? Why must I be a ‘baby’? But Brooke, like a few other people who shall remain nameless, were right to call me a baby feminist. I hadn’t done the intellectual labor yet to fully understand and define what my feminism was. Yes, at the base level all feminists believe in social, political, and economic equality with men. But like any ideology, there are dissenting opinions and contradictory beliefs to be found. I had little understanding of black feminist history, and that impacted my ability to think critically. So with that memory in mind, I created this primer to educate those who are unfamiliar with the history of black feminism.

The history of black feminism is expansive, but I sought to provide key highlights in this primer.

I hope that if you’re reading this, you’re doing so with an open mind. Rather than discussing black feminism as an ideology, I will be focusing on its history. Quite often feminism is written off by people in the black community as a contrivance of white women, a hindrance to black progression, or something blown out of proportion by crazy and lonely women on the internet. I will address all of that and more in this primer.

So What Had Happened Was…

The true birth of white feminism occurred during the abolitionist movement of the 19th century. Middle-class white women didn’t work, and social reform granted a new type of independence. The same was true for the smattering of free middle-class black women, who also established their own anti-slavery societies. It should be noted that integrated anti-slavery societies were rare, though various segregated groups did collaborate for events. For many of the women who participated in gaining freedom for slaves, it was the first time they had participated in anything remotely political, and it invigorated their interest in other lanes of social justice. So when emancipation came, many turned their interests to the temperance movement and gaining suffrage. Support for the 15th amendment (which would give black men the right to vote) fractured old alliances between black abolitionists and white ones. “I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work or demand the ballot for the negro and not the woman,” claimed Susan B. Anthony. Numerous other white suffragettes agreed with this sentiment, leaving women like Sojourner Truth in the crossfire. Sojourner was a former slave who stirred white emotions with her passionate (and partly fabricated) “Aint I A Woman” speech in 1851.

I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman’s rights. [sic] I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I have heard much about the sexes being equal. I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am as strong as any man that is now. As for intellect, all I can say is, if a woman have a pint, and a man a quart – why can’t she have her little pint full? You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much, – for we can’t take more than our pint’ll hold.

Unfortunately, Sojourner considered white women to be her intellectual superiors and therefore sided with white women who believed black men did not deserve the right to vote. Then there was Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, who understood that black men’s liberation did not guarantee that of black women. She said in 1867:

“There is a great stir bout colored men getting their rights, but not a word about the colored women; and if colored men get their rights and not colored women theirs, the colored men will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before.”

In Da Club: The Extraordinary Magic of Black Clubwomen

WOMEN’S CLUB OF BUFFALO, NEW YORK, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS.

WOMEN’S CLUB OF BUFFALO, NEW YORK, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS.

Black women were often excluded from conversations about womanhood. The Worlds Congress of Representative Women took place in 1893 at the Chicago World’s Fair and had 500 speakers. Only five were black women. Clearly, black women were not being represented. But they were also neglected by black leaders on conversations about blackness. When W.E.B. Dubois called upon the talented tenth, he directly addressed men. So middle-class black women with the means to do so began organizing clubs around the country in the years during and after reconstruction.

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin was the daughter of a black man and a white woman. She grew up privileged and educated in comparison to many of her peers. In 1894 she published The WomansEra, the first newspaper created by and for black women. She became the organizer of the National Federation of Afro American Women. she published an 1895 letter accusing black women of having “no sense of virtue” and alleging they were “altogether without character.” The letter had been written by a white man angry about Ida B. Well’s anti-lynching campaign. She distributed this letter to various black women’s clubs to get them to organize for the First National Conference of Colored Women in America in 1895. It was here that Booker T. Washington’s wife Margaret addressed the sharp class divide among black women and what it meant for the middle-class black women present. According to Anthony Neal, she noted that middle-class black women had been given opportunities to evolve “mentally, physically, morally, spiritually and financially” and that many black women had been deprived of that opportunity by slavery. She urged members of the former class to do all they could to uplift and inspire the latter, reasoning that individual success was not enough; that only by “lifting as we climb” was it possible for the race to make progress.

By 1896, they all came together as the National Association of Colored Women. “Lifting as We Climb” was implemented as the club motto for the National Association of Colored Women when it was established the next year. They understood that they needed to help their lower-class brothers and sisters, and this reflected in their goals, which included:

-Gaining suffrage (some were also very active in the temperance movement)

-Being role models for lower class black women, who they believed were targets of sexual predators because of their behavior/dress

-Ending lynching and other racial violence

-Providing information about sexual health and hygiene

-Providing food/clothing/shelter for the underprivileged

Even still, these women were a reflection of their time. They were concerned with respectability politics and some even subscribed to beliefs and attitudes that would get them “canceled” by today’s standards. For instance, they would have been considered “pick mes” for their strict adherence to the mainstream desire for marriage.

We can’t talk about this era without mentioning Anna Julia Cooper. (1858-1964)

We can’t talk about this era without mentioning Anna Julia Cooper. (1858-1964)

She was a graduate of Oberlin College and obtained a PhD from the prestigious Sorbonne in France. She believed that if given the right tools, all black youth (male and female) could excel. She was also an outspoken suffragist. But it was her 1892 publication of A Voice From The South that made her so iconic. In what is considered the first book of black feminist thought, Mrs. Cooper made the connection between race and gender as tools of oppression. She also encouraged black women to tell their stories, rather than to let white people or black men do it. Speaking of black men, she criticised them and the church for failing to uplift black women. That same year, Fredrick Douglass was reported as saying, “I have thus far seen no book of importance written by a negro woman and I know of no one among us who can appropriately be called famous.” By 1894 Mrs. Cooper was preaching the importance of black women’s clubs distinguishing themselves from white ones by focusing on issues unique to black women.

Other notable club women (apart from Ida B. Wells, who is probably the most celebrated black women of the era) include:

Mary Church Terrell (1863-1954)

She was born to mixed-race former slaves who stressed the importance of education and was one of the first black women to graduate from college (Oberlin University in 1884). While serving as the head of the National Association of Colored Women, under the pen name Euphemia Kirk she published stories in black and white newspapers about the black clubwomen’s movement. She also spoke at the International Congress of Women in Berlin in 1904, the only black woman to do so. She was also a founding member of the NAACP.

Frances Harper (1825-1911)

In addition to helping slaves escape along the underground railroad, Ms. Harper gave a speech in 1866 before that National Women’s Rights Convention and demanded rights for everyone, including black women. She was so upset with white suffragist and racist Frances Willard for not showing concern for black women that she helped organize the National Association of Colored Women. Additionally, Frances published her first book of poetry at 20 and was the first black woman to publish a short story, 1959’s The Two Offers.

Fannie Barrier Williams (1855-1944)

Fannie began her career as a teacher but eventually came to be a lecturer on suffrage, especially for black women. She helped found the National League of Colored Women in 1893 and the National Association of Colored Women in 1896. In 1894 she was nominated to be a member of the white Chicago Women’s Club, and received death threats and caused so much commotion that her membership process was stalled for two years.

After women gained the right to vote and the temperance movement gave way to prohibition, both the white and black club women movements fizzled. With the litany of war and racial injustices, women’s rights were put on the back burner.

“Where Are The Ladies At?” Black Womanhood During The Fight Against Jim Crow

Thanks to the efforts of 19th and early 20th-century black clubwomen, there were larger numbers of women attending college and getting better jobs than the generation before them. However, the overwhelming majority of black women toiled away in poverty during Jim Crow. Black womanhood often meant getting a menial job at an early age, having children at an early age, and receiving a limited education. Social mobility was limited, especially for those women who lived in rural southern communities plagued by violent racism in the form of arson, lynching, and destruction. Rape was commonplace for domestic servants, an occupation largely filled by poor black women who could not fight back because they had families to take care of. Black women were also routinely sterilized by nefarious doctors and local governments without their consent as a means of population control. Then there was, of course, the violence inflicted on them by their own men. Marital rape was not illegal. Domestic violence barely received a batted eye. Black women were placed in a precarious position: defend their men at all costs while also enduring abuse. This made them think of themselves and the burgeoning women’s movement differently than white women. For instance, white women wanted the ability to work outside of the home. This was something most black women did already. Clearly, womanhood meant something different for black women. Said Toni Morrisson:

“For years in this country there was no one for black men to vent their rage on except black women. And for years black women accepted that rage, even regarded that acceptance as their unpleasant duty. But in so doing they frequently kicked back, and they never seem to have become the true slaves that white women see in their own history. True, the black woman did the housework, the drudgery; true, she reared the children, often alone, but she did all that while occupying a place on the job market a place her mate could not get or which his pride would not accept…. so she combined being a responsible person with being a female.”

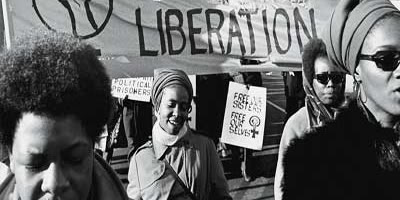

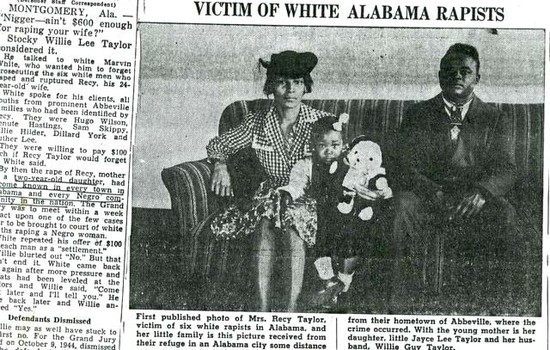

So when the plight of the black man took center stage for most civil rights and black power leaders during the 50s, 60s, and 70s, many black women had few qualms about this. It was normal to put race before gender. That’s not to say black women continued to ignore unique issues, however. For instance, after the 1944 rape of Recy Taylor, Rosa Parks organized the Committee for Equal Justice for the Rights of Mrs. Recy Taylor to bring awareness to the sexual violence perpetrated against black women. I find it worth mentioning that things like this aren’t mentioned in public school history books. Violence committed against black women is largely scrapped for re-tellings of violence against black males, like Emmett Till. But this is a reflection of how women’s issues were treated by the civil rights and black power movements.

One thing that men of these movements grappled with was considering black women not only as their social equals but as intellectual equals. Martin Luther King Jr. was noted by many of his contemporaries as writing off the ideas of his female peers or keeping them from leadership positions. Said one of his assistants, Andrew Young:

“We had a hard time with domineering women in SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership Conference) because Martin’s mother, quiet as she was, was really a strong, domineering force in the family. She was never publicly saying anything but she ran Daddy King, and she ran the church and she ran Martin, and Martin’s problem in the early days of the movement was directly related to his need to be free of that strong matriarchal influence.”

In 1965, The Negro Family: The Case For National Action was published by Daniel Moynihan. In it, he painted a bleak picture of dominant matriarchs, effeminate black boys, and unhealthy families. It was less harsh than an earlier report by black sociologist E. Franklin Frazier, but it still legitimized the thoughts of many black leaders concerned with the power of black women. Therefore it is no surprise that many of the speeches from around this time by prominent civil rights and black power leaders include rhetoric about re-establishing the black family and black manhood. “The year 1966 shall be remembered as the year we left our imposed status as Negroes and became black men,” said CORE leader Floyd McKissick. Women who asserted themselves and attempted to fulfill leadership positions were seen to be “castrators.” Recalled Angela Davis about her experiences with the Los Angeles chapter of SNCC: “Some of the brothers came around only for staff meetings (sometimes), and whenever we women were involved in something important, they began to talk about “women taking over the organization”- calling it a matriarchal coup d’etat.”

This was an especially common theme in the aftermath of Martin Luther King Jr’s death, as black leaders began to see violent revolution as the inevitable next step. Strong black men were needed for this battle, not women or emasculated men. By the way, “emasculated” black men were blamed on black mothers and matriarchal households. Black women were characterized as too strong, masculine, and un-feminine to the point that it threatened black manhood. One of the most popular black books of 1968, Black Rage, written by a pair of psychologists, alleged that black women:

“did not experience the compensatory blossoming of narcissism found in women of other races. So they stopped competing for male attention, allowed themselves to become overweight, and their sexual lives became perverted.” (Paula Giddings)

Unsurprisingly, many black women agreed with the popular thought that black women needed to soften themselves so that black men could take over as the rightful leaders of the fight for liberation. Said activist Joyce Ladner, “The ‘traditional strong’ black woman has probably outlived her usefulness because this role has been challenged by the black man.” And so, most women recoiled at the idea of joining a fight for womanhood, as they saw it as abandoning black men. By having independence and being assertive, they were not only ruining the family but destroying the black race. Even still, many black men and black women endorsed the Equal Rights Amendment, a longstanding bill that was re-introduced to the public consciousness in 1971.

“The womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender”: Developing Black Feminist Thought in the 70s and 80s

Paula Giddings detailed in When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and America how the 1972 presidential campaign of Shirley Chisolm exposed the blind spots of both the black power movement and the feminist movement. She was left high and dry by high-powered feminists like Gloria Steinem, and black leaders accused her of being “captive of the women’s movement.” While black leaders scrambled to find a political candidate to endorse in 1972, nearly all of them ignored Shirley Chisolm. The only group to endorse her was the Black Panthers, and they did NOT have political clout. When Chisolm lost the Democratic primary to George McGovern, she felt that sexism impacted her campaign more than racism.

One interesting quagmire from the early 70s that further divided black women and men and even caused internal battles among black feminists was the fight for abortion rights. The concept of abortion clashed with reigning popular thought about black womanhood, especially since some leaders believed and preached that black women could best serve their community by increasing our population and staying shackled to the home. The forced sterilization of black women over the past decades didn’t help matters. From Paula Giddings:

“A May 1969 issue of The Liberator warned, “For us to speak in favor of birth control for Afro-Americans would be comparable to speaking in favor of genocide.” A year earlier, and Ebony article had published the views of a physician who saw a revolutionary baby boom as a tactical advantage. He believed if black women kept producing babies, whites would have to either kill blacks or grant them full citizenship.”

We’re still having arguments about abortion as genocide today.

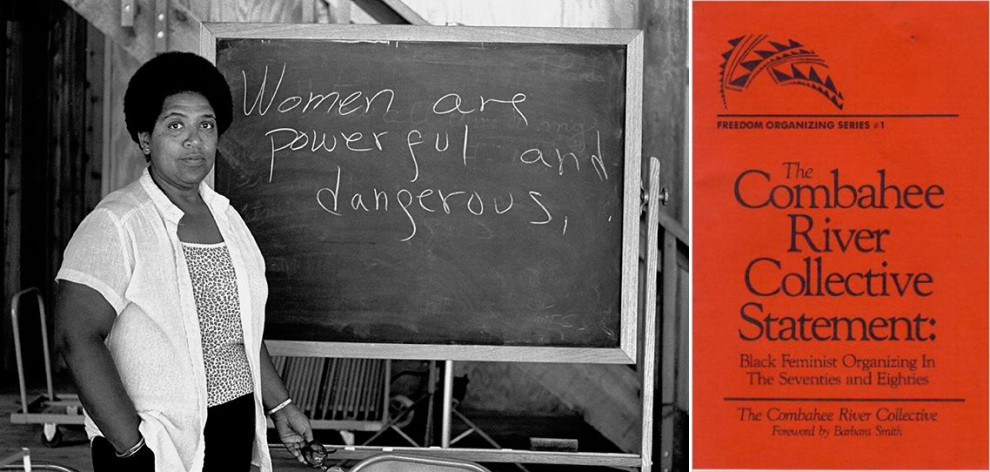

This, along with the treatment of black women during the civil rights and black power movements, was followed by a renewed interest in exploring black women’s rights. In a remarkable similarity to 19th-century club women, “radical” black women began organizing and writing. In 1973, the short-lived National Black Feminist Organization was established. It was followed by the Combahee River Collective in 1974, so named because Harriet Tubman led a military campaign that freed 750 slaves near the river. The Combahee River Collective Statement was developed thanks to weekly meetings and sporadic retreats held in the northeast. In addition to establishing objectives and theories, they coined the term “identity politics”, and like Anna Julia Cooper a century before, encouraged black women to write their stories and ideas and get them published. After all, this was the most literate generation of black women to ever exist. Establishing black feminist scholarship was crucial.

In 1982, But Some Of Us Are Brave: All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men: Black Women’s Studies, edited by Gloria T. Hull, Patricia Bell Scott, and Barbara Smith, sent shockwaves through academic circles. These feminists worked to define what black feminism was and how to help black women. Another important discussion among black feminists at this time was the legitimacy of lesbianism as a sexual orientation in the shadows of intense national homophobia during the mid-twentieth century. Though the term “intersectionality” would not be coined until 1987 by Kimberl’e Crenshaw, black feminist thinkers were already thinking within that framework during the 1970s and early 80s. At the forefront of these conversations were women like Audre Lorde, who in particular frequently clashed with mainstream white feminists. This quickly isolated her as an angry black feminist. Her faux pa? She [rightfully] claimed that white feminists contributed to the oppression of black women. She and other black women were disgusted with the racism they faced in women’ss organizations. At a 1981 conference for the National Women’s Studies Association, she said:

“I speak out of direct and particular anger at an academic conference, and a white woman says, ‘Tell me how you feel but don’t say it too harshly or I cannot hear you.’ But is it my manner that keeps her from hearing, or the threat of a message that her life may change?”

Black feminist scholars continued to experience racism within the National Women’s Studies Association, so they staged a large walk-out at an Akron, Ohio conference in 1990.

But perhaps the largest battle for black feminists was actually defining black feminism. Some women, like Alice Walker, wanted to eschew the label altogether. She coined the term “womanism”, which, while advocating for equality to men in the same manner as feminism, differs from “black feminism” in a few ways:

- Womanists believe there can be no shared fight with white feminists due to racism

- Womanists believe that blackness (or one’s culture) is not apart of her feminist views, but rather how she views her femininity

- Womanism contains some black nationalist discourse, with a branch called “Africana Womanism” advocating for familial units over individual womanhood. Established in the 90s, Africana Womanist creator Clenora Hudson-Weems saw feminism as man-hating, and believed that it wasn’t something that black women could connect to, as feminism was established to cater to white women

- Many womanists yearn for a world where men and women can coexist AND maintain differences

The most important concept to emerge from this era was intersectionality, as it set the stage for modern black feminists, who rage against ableism, transphobia, and homophobia more than past feminists ever did. In 1976, the court case DeGraffenreid v. General Motors occurred. When a group of black women were fired from General Motors in St. Louis, they noticed that a white female employee who had been hired after them was allowed to stay at the company. Outraged, they sued General Motors and claimed they had been discriminated against on the basis of race and gender. The courts ultimately decided against them, citing that they couldn’t have been discriminated against because black men and white women both worked at the factory. The court did not consider the fact that black women were apart of neither group. The court decided they “could not combine the claims” of race and sex discrimination because it would be “beyond the scope of Title VII.” This case is regularly mentioned by Kimberl’e Crenshaw, and demonstrates the importance of intersectional feminism penetrating mainstream society.

The Nineties To Now (Black Feminism During Third Wave Feminism)

A defining moment for black feminism was the public condemnation of Anita Hill in 1991, who accused black Supreme Court Justice nominee Clarence Thomas of sexual harassment in the workplace. Males- both black and white- did not believe her, and she was called everything from crazy to the instigator of a lynch hunt against a black man. It was a familiar theme, but with the increasing visibility of black feminist thought in academic circles, the call for intersectional feminism only seemed more legitimate. At the helm of this discussion was Rebecca Walker, daughter of Alice Walker, who established herself as a “third wave feminist” in a 1992 article entitled “Becoming the Third Wave”. She went on to establish the Third Wave Fund, an initiative hell-bent on getting young women interested in activism and leadership roles. In 1995, African Americans Against Violence was formed by Reena Walker in opposition to a parade organized by Al Sharpton for convicted rapist and woman beater Mike Tyson. The women successfully caused the parade to be canceled, and they were ultimately accused of catering to white feminists.

As you may have noticed in the previous sections, in the present day we’re having the same arguments over what black womanhood is, how we are oppressed, and how we can battle said oppression. Fortunately, more black men (and women) than ever are aligning themselves with intersectional feminist views. In part, we can thank black women like Salt N Peppa, Queen Latifah, Missy Elliot, Lil Kim, and others who established themselves in hip-hop as equal to men (even if they didn’t use the term feminist to describe themselves). We also must thank writers like bell hooks and Patricia Hill Collins, whose writings make up entire college courses. We can also thank the explosion of the internet, as once esoteric feminist ideas and history have infiltrated the most patriarchal of knitting circles.

Often people ask why feminism is still needed as if all of women’s problems have been solved. Usually, they toss out the obvious things: we can vote, we can work (lol), we can make our own choices. Its true, we have made amazing progress. But the fight is not over. Today’s black feminists busy themselves with a plethora of issues, included but not limited to:

- The domestic and sexual violence committed against black children and women. A major issue is a domestic homicide, in which 50% of all women killed by a former lover are black.

- The eradication of sex trafficking

- Treatment of black women at the hands of police and in prison (because women are often missing from critiques of police brutality)

- Women’s reproductive rights, as well as high infant and maternal mortality rates caused by stress, poor environments, and bad health

- The end of slut-shaming, toxic masculinity, and other facets of rape culture

- Visibility/safety/representation for marginalized black women- like the disabled, trans, and queer, or those in sex work

- The income gap between the races and the genders

- Lack of adequate representation in politics and Hollywood

- Self-esteem and self-love among black girls

All the while, most black feminists also do their part to contribute to the overall movement for black empowerment and justice. Don’t believe me? Look up who founded Black Lives Matter.

In modern discussions of black feminism, often what’s missing is the entire history that I just laid out for you. Many black women have no idea that they are repeating the mistakes of their ancestors during the civil rights and black power movements by patronizing the fragile egos of misogynistic black men. Many black men have no idea that they are blatantly wrong when they claim that black feminists have been brainwashed by white feminists, and are destroying the black community. So, of course, our remedy is to make the history of black feminism more accessible. There will continue to be differing thoughts in black feminism like with any ideology, but for now, we must do our duty in erasing the notions that black feminism harms the community or that it is a relatively new contrivance that undermines black progression. There is a history, and we all need to know about it.

“Only the black woman can say ‘when and where I enter, in the quiet, undisputed dignity of my womanhood, without violence and without suing or special patronage, then and there the whole Negro race enters with me.” (Anna Julia Cooper)

Essential Reading List

If you want to read more about gender and feminism so that you can draw your own conclusions, these books/pamphlets are essential.

- When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America (Paula Giddings)

- Women, Race, and Class (Angela Y. Davis)

- Aint I A Woman? Black Women and Feminism (bell hooks)

- Black Feminist Thought (Patricia Hill Collins)

- Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty (Dorothy Roberts)

- Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America (Melissa Harris-Perry)

- Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Audre Lorde)

- Black Women’s Manifesto; Double Jeopardy: To Be Black and Female (Frances Beal)

- “Ar’n’t I a Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation South” (Deborah Gray White)

Additional Sources

- Anna Julia Cooper and Africana Womanism: Some Early Conceptual Contributions (LaRese Hubbard)

- Mississippi’s First Labour Union (Ken Lawrence)

- When and Where I Enter: The Racist Expectations of Whites Only Feminism (Kirsten West Savali)

- ‘ The Only Position For Women in SNCC is Prone”: Stokely Carmichael and the Percieved Patriarchy of Civil Rights Organisations in America (Sabina Peck)

- Memories Of a Proper Girl Who Was A Panther (Somini Sengupta)

- Reflections Unheard: Black Women in Civil Rights (Documentary by Nevline Nnaji)