I remember when I first saw Solange’s big chop. At the time, I was so confused. I was one of the many people who called it ugly. I looked at her face without hair framing it and became repulsed. This was in 2009, the same year I was a freshman in high school. My own hair was often doobie wrapped or flat ironed to a crisp. My hair never grew past the nape of my neck, and was often puffy at the roots from new growth. I jumped at every chance I got to get my hair slicked down under a wig cap and camouflaged by a glued quick weave. Whenever my hair was replaced with yaki hair, I felt beautiful. I didn’t get my first taste of virgin hair until 11th grade. So when I saw Solange, who had money and hairstylists, with short natural hair, it didn’t make sense. As Solange’s big chop grew into a beautiful crown, I stubbornly permed the hell out of my hair for the next few years and sat through hundreds of hours of sew-in applications. Seeing Chris Rock’s “Good Hair” didn’t even change my mind. I struck down any suggestion to “go natural” from multiple friends during my freshman year of college. It wasn’t until sophomore year, after a perm gone wrong and a realization that unhealthy straight hair was uglier than healthy natural hair, that I made the big chop. I’ll never forget the feeling. My head felt lighter. I felt lighter. Ever since then I have never seen a head of natural hair that I didn’t like.

Disclaimer: I don’t deny that black men have had their own issues with natural hair, but this problem has ALWAYS been a much bigger issue for black women.

Before slavery, an African woman’s hair meant various things depending on the region and culture she hailed from. Maintaining hair was important and sacred, because it was a non-verbal tool for communicating tribe affiliations, age, marital status, and more. African women were surrounded by resources for their hair, like Shea and palm oils. They had time to actually do their hair. To put it simply, an African woman’s hair was an integral part of her identity.

During slavery, hair styles and maintenance changed because the identity of the black woman changed. For one thing, on some plantations slave women were not allowed to wear anything but scarves. Some southern states made scarves a requirement for slave women to distinguish them from free black women. Headscarves were associated with low status and destitution. It was an ugly mark of inferiority. But scarves weren’t the only way that slave women were made to feel aesthetically inferior. Without access to proper hair care products of the day, many slave women resorted to using toxic substances like kerosene, butter, and animal fat on their fragile strands. You also have to remember they often didn’t have the time required for maintenance like washing, conditioning, and twisting… especially if they worked from sun up to sun down. For many, hair maintenance meant frequent braids, scarves, and dry misshapen Afros. With broken ends, damaged edges, and a plethora of stress to compound any damage from toxic chemicals, black hair was considered unattractive. It was shamed by white society and brainwashed black folk. The good hair versus bad hair dynamic was intensified from the not-so-subtle battle between house slaves and field slaves. Straight and fine hair was a white characteristic, and because whiteness was idealized it was made the standard of beauty among black people as well.

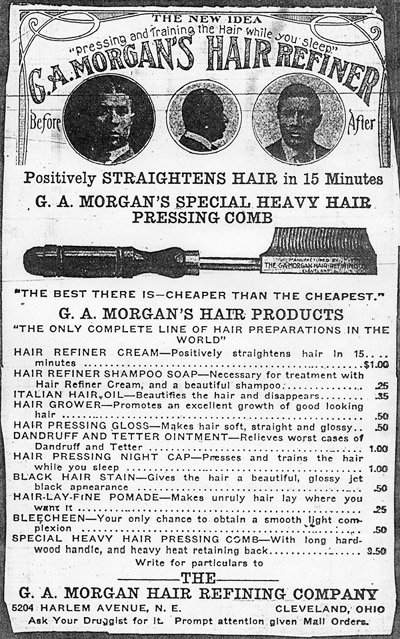

After emancipation, kinky and braided hair was negatively associated with slavery. Kinky unkempt hair not only reminded black women of the terrors and abuses of bondage, but also terrified disgusted white society. So, black innovators set to work to find a way for black women to avoid negative comparisons to white women and their long and fine tendrils. Some women mixed lye and potato for straightened hair with disastrous results. Annie Malone entered the scene in the 1890’s, with a primitive version of a relaxer. She eventually went on to create a door to door hair care company that included a popular “hair grower”. In 1909, Garrett A Morgan noticed the chemical he was using had inadvertently straightened curly wooden fibers. He used the chemical to create a relaxer, which he started selling to men before finding a strong consumer base in black women. He also sold a pretty popping hot comb.

After emancipation, kinky and braided hair was negatively associated with slavery. Kinky unkempt hair not only reminded black women of the terrors and abuses of bondage, but also terrified disgusted white society. So, black innovators set to work to find a way for black women to avoid negative comparisons to white women and their long and fine tendrils. Some women mixed lye and potato for straightened hair with disastrous results. Annie Malone entered the scene in the 1890’s, with a primitive version of a relaxer. She eventually went on to create a door to door hair care company that included a popular “hair grower”. In 1909, Garrett A Morgan noticed the chemical he was using had inadvertently straightened curly wooden fibers. He used the chemical to create a relaxer, which he started selling to men before finding a strong consumer base in black women. He also sold a pretty popping hot comb.

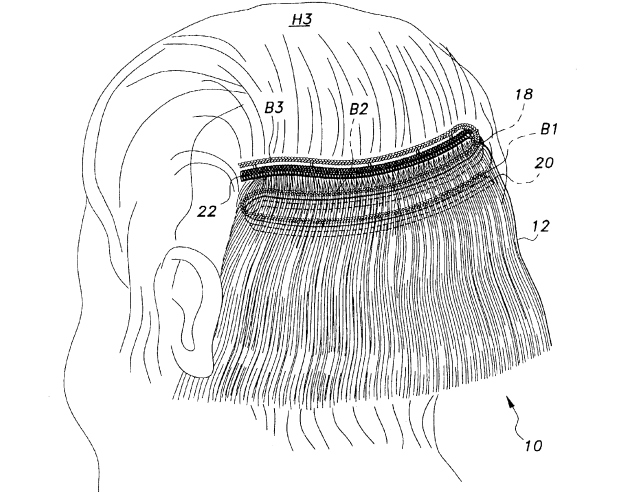

By 1912, hot combs were growing in popularity among black women as a way to straighten hair. Madam CJ Walker’s hair products also flourished during this time. Most black women were desperate for not only straightened hair, but hair that grew. Going to the local beauty shop for hair maintenance gradually became a popular weekly to biweekly expense. Like black barbershops, black beauty salons flourished in our communities. From the 1920’s-1960’s black women stayed on par with national styles of the day, for both assimilation and trend value. Many black social clubs required that black women be of the right complexion and hair grade. The 1920’s saw the popularity of finger waves. The 1930’s were filled with low maintenance roller curl looks, which could be explained by the Great Depression. It’s important to note that roller curls were NOT anything like natural curls. The 1940’s, the years of the war, saw a lot of up-dos, thanks to the styles of factory working women everywhere. Throughout this time black women also wore wigs to achieve mainstream hairstyles. But in 1951, Christina Jenkins obtained a patent for what would become the foundation of the sew in. Before her process, people used bobby pins to secure weave to their scalps. The process she created was a long one, and resulted in a bulkiness and stiffness that would get you clowned today- but it was an innovative style for mid century black women.

to achieve mainstream hairstyles. But in 1951, Christina Jenkins obtained a patent for what would become the foundation of the sew in. Before her process, people used bobby pins to secure weave to their scalps. The process she created was a long one, and resulted in a bulkiness and stiffness that would get you clowned today- but it was an innovative style for mid century black women.

Maintaining straight and mainstream hair was socially important to black women well into the late 60’s, but the pro-black movement brought out a lot of never before seen afros. Influenced by the likes of Angela Davis, Kathleen Cleaver, and others, natural hair was more of a statement against the establishment than it was a lifestyle choice.

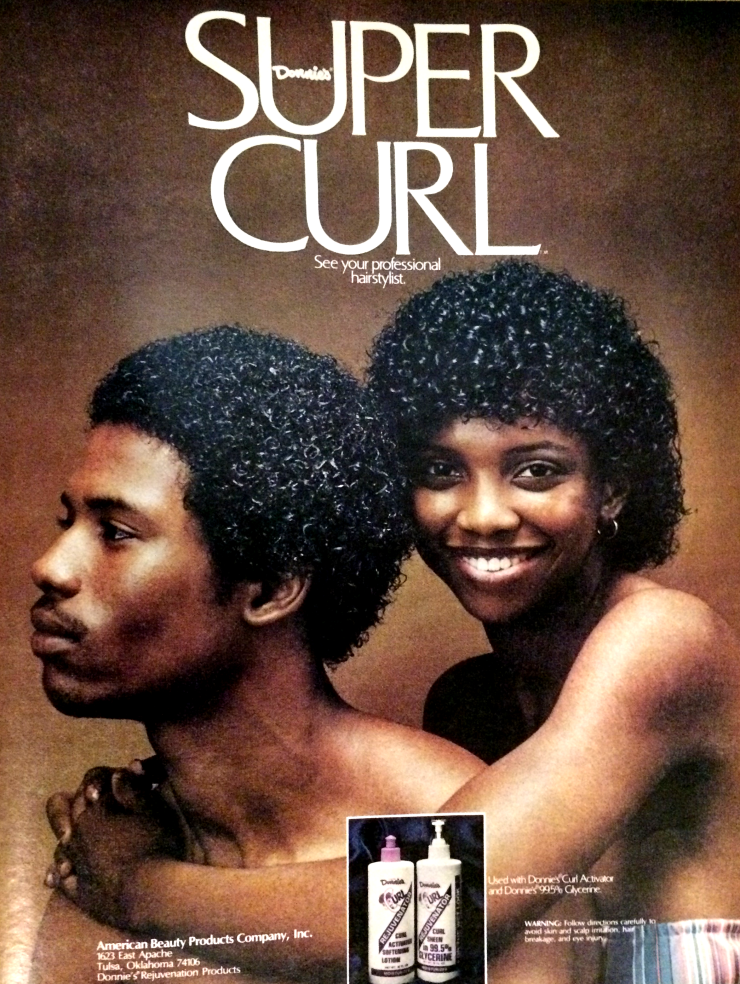

Kinky hair had scared and offended white America from the very beginning and that didn’t suddenly change in the 70’s. A black woman wearing her hair natural was a personal choice that could bring about a lot of criticism. During the pro-black movement and especially after it began to slow down, wearing an afro could run you the risk of appearing militant, troublesome, and unemployable. But it wasn’t just an unappealing choice to white people. Even folks in the black community saw natural hair as unattractive and the mark of radicalism. It also didn’t help that shrinkage encouraged those “bald-headed scalawag” jokes we all remember from our childhoods. Natural hair wouldn’t truly catch on in the mainstream black community until the 21st century, after the Jherri Curls, feathered hair, and yaki quick weaves prominently ran amok from the late 70’s to early 2000’s. But making the choice to wear natural hair still isn’t easy today. Natural hair is at risk of being called unprofessional in the workplace. Hairstyles largely worn by black Americans, like braids and dreadlocks, are banned by certain employers. Friends and family members ask you what happened to your old style after debuting your big chop instead of giving a reassuring compliment.

Throughout American history the black woman’s hair has been debated and demonized by every race and gender. Natural hair is ugly. Wearing flaming red weave is too much, but brown 14 inch Indian Wavy is just right (and better than a tight 4C afro). If you wear weave or straighten your hair, you’re self hating. If you dye your natural hair blonde or wear blonde weave you’re REALLY self hating. If you’re bald, you’re ugly. Braids are ghetto. Headscarves in public are ratchet.

ENOUGH.

Im tired of it. At the end of the day, through all of the irrelevant opinions, a few facts have emerged:

- Black women’s hair choices have been influenced or limited by employment opportunities and status. The choices we have historically made about our hair (and that some of us still make) are to blend in to white society.

- Natural hair has largely been vilified up until the 2000’s. It has gone from a political statement to a true lifestyle.

- Whether rocking an afro or pulling up to the function in butt length aqua blue Malaysian curly, black women can wear ANY hairstyle and get away with it. Don’t @ me. Matter of fact, dont @ any black woman with negativity about their hair (unless they’re being malignant and a track is showing or their wig is too shiny, you’ve got every right to comment).

I love changing up my look with extensions. I crave trips to the beauty supply store to look at products for my own hair and to try on new wigs. I adore my afro- but I’ll admit it took a long time for me to get to this place. It took me a long time to see beauty in my tight curls. But when acceptance came, it took over. There is nothing anybody can tell me about my beautiful crown. When I first saw Solange’s big chop, it was unnerving. She wore it confidently, and that was the scary part. My whole life, natural hair that wasn’t loosed mixed girl curls was ugly. “Natural hair isn’t for everybody”, girls and women everywhere said, patting the itchy roots of their Brazilian deep wave or running a comb through their long relaxed strands. Throughout American history we were made to hate our natural hair and see it as inferior to white women- but there was Solange, holding her head high. Thanks, girl.