Disclaimer #1- “Black Churches” is an umbrella term. It is not meant to be monolithic. The thousands of black churches that have and continue to exist on American soil were carved by regional differences. At no point in the following paragraphs do I mean to imply that every black church is the same. Instead, I want to talk about the many similar aspects of black church culture that have impacted our collective experiences.

Disclaimer #2- White churches are not immune from the bad and the ugly mentioned in these paragraphs, but as a black woman my concern lies with black church culture and its effects on my people.

I was 12 or 13 years old when I began hating going to church. Before puberty, I was a good Christian girl who liked going to Sunday school and adored her 400-page tome of children’s bible stories. I said my prayers nightly and I honestly believed that God would make me choke on my food if I didn’t say grace. When my attraction to girls became radically clear around the age of 9, I prayed to God to take my affliction away. Not wanting to be doomed to the fiery pits of hell, I revved up my dedication to him. A few friends and associates from sixth grade remember my desire to be a preacher, and my annoying habit of pointing out sin or reciting biblical verses. On the outside, I was a passionate Jesus freak. On the inside, I was bursting with questions. Questions with answers that the church couldn’t provide. Soon after, my southern Baptist church became a sweatbox of guilt and confusion. These two things eventually gave way to skepticism. Everything changed. I despised waking up early on Sundays, abhorred sitting still and listening to sermon for two hours (more if the preacher was feeling frisky), and I absolutely loathed lingering in the church parking lot after service. I’d encounter snooty gossip, noxious cigarette smoke, and sneaky side-eyes between cliques of women doling out Fashion Fair coated smiles. I often wiggled out of too tight hugs from the deacon, who always supplied pocket candy to all the little girls, his friendly forehead kisses just a little too wet and a little too frequent.

My mom didn’t go to church regularly, but once or twice a month she’d corner me on a Saturday night with those devastating words. “We going to church tomorrow.” Eventually I was too old to be dragged to church, eyes rolling and chest heaving with boredom. I made sure to work eight hour shifts on Sunday when I began working at a grocery store at 15, and that was that. I haven’t been back to church since. At no point in the past eight years have I desired to enter one, either. When I’m feeling lonely, sad, or broke, the thought of church does not cross my mind. In the black community, I am a minority.

According to the Pew Research Center, 78% of black Americans belong to a protestant church. 59% belong to historically black churches, like the African Methodist Episcopal Church and the National Baptist Convention. These entities have survived years of racial warfare, serving as battlegrounds and healing wards for our people when no other places would. The First African Baptist Church is believed to be the oldest black place of worship in America, getting its start in Savannah, Georgia in 1777. A smattering of other black churches existed later throughout the lower states, terrifying white southerners with every meeting held within their walls. This fear was rooted in the threat of insurrection from blacks, and it drove many southerners to control what access slaves had to safe black spaces. So many slaves were forced to go to white churches with their masters and made to stand in the back, absorbing lessons about being obedient and good. Others were visited by designated black preachers who delivered special sermons that emphasized rewards for pain in the after-life. In the north, segregated white churches created the need for black ones. In 1808, black Americans and Ethiopian merchants established the Abyssinian Baptist Church in New York after being discriminated against in a white church. In the post-antebellum, numerous black congregations broke off from integrated churches to do their own thing. Black churches granted agency and freedom, at least within their hallowed halls. Black Americans could now worship where they saw fit- and black churches became more popping than ever. Black people no longer had to sit in the back, or in the rafters. In the south, they were no longer forced to listen to messages about accepting black subservience. Different styles were developed and various denominations were observed… but there were a few similarities between these establishments that both catalyzed and hindered black progression.

The Good

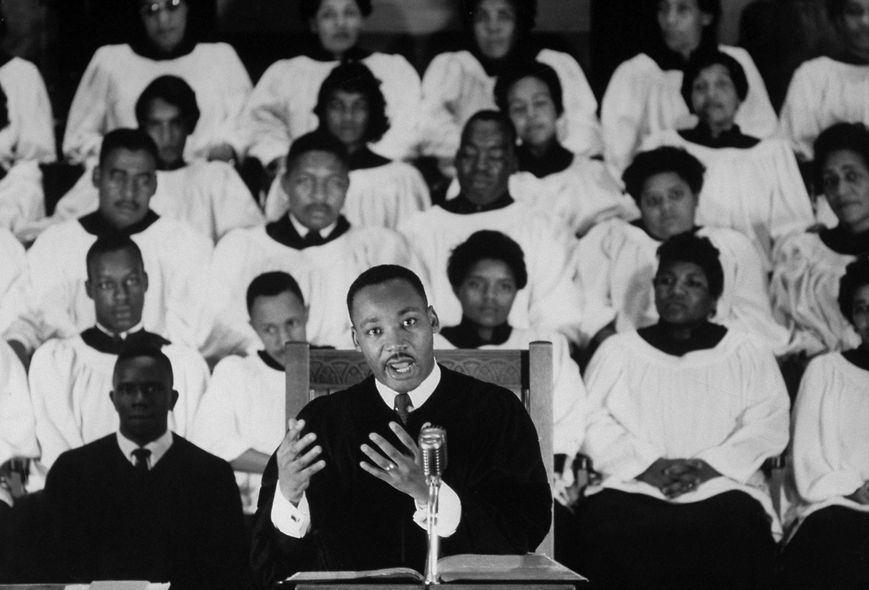

The black churches sense of community is both a blessing and a curse. It’s importance and authority has allowed it to be a frequent target of exploitation. But to address the bad and the ugly, we must talk about what makes the church so good. What makes it such a pillar in our community? Statistics show that black people are more likely to go to church than their peers. This is because the black church was, and continues to be, a safe haven. It shelters its flock from hunger, ignorance, white society, and the elements… and has been doing so for years. During reconstruction and Jim Crow, it was black churches doling out meals, administering educations, and organizing clothing drives. The church provided a sense of community and kinship that no other organization has. That is why it was a powerful hub of political and social activity during the fight for civil rights. It was where leaders and common folk gathered for news and strategizing. Without the black church, the civil rights movement wouldn’t have happened. Lastly, on a more trivial level, many of our black music legends got their start in black churches.

These are good things. Things that no black atheist, Muslim, Jew, or agnostic can deny. Unfortunately, the good does not obscure the bad, and it damned sure doesn’t hide the ugly.

The Bad

When it was revealed that Wells Fargo sent black employees to black churches to push costly subprime loans, I wasn’t surprised. When white politicians flex and pose in photo opps with black church leaders and later stay silent on relevant black issues post-election, again I’m not surprised. Because black ministers have historically had to fulfill the additional role of political leader, they were often subject to racial agendas that threaten to unravel what the church itself was trying to encourage- progression. Henry Ford, white American hero, donated to black churches and threatened to cut off support to those who didn’t discourage labor unions among congregants. In the 1920s Ford employed about 1600 workers in Detroit, and they were assigned to the dirtiest and dangerous of jobs. Growing increasingly frustrated with immigrant employees looking to unionize, Henry Ford made sure to cozy up to various black church leaders throughout the 20s and 30s, on the lookout for “very high type fellows- those who were not black militants.” Using the black church like a twisted job fair, Henry Ford sought to build a constituency of workers to be loyal to him. In the process of securing jobs for their congregants by being cool with Henry Ford, pastors became indebted to him politically.

This reminds me of black pastors who —knowingly or unknowingly— aligned themselves with the enemy during the Bush administration. Prominent black pastors joined the predominately white Christian right to attack the LGBT community. Why? They “were on board and in hot pursuit of the federal faith based funding that represented relief and an opportunity to expand their ministries.” Reverend T.J. Graham of Nashville said he’d support Klansmen at his anti-gay rallies. Reverend James Meeks of Chicago is virulently anti-gay, and is one of the leading voices in anti-gay marriage legislation in Illinois. But the biggest name of all was Bishop Eddie Long, of New Birth Baptist Church. For both aligning himself with the white Christian right and his degradation of black LGBT, he received one million dollars from the US Administration for Children and Families. Other ministers from T.D. Jakes to Willie Wilson have been noted for pushing homophobia onto their flocks, despite the central message of Christianity being about loving thy neighbor. But, it’s deeper than that.

The black pastor is expected to lead his flock selflessly. Unfortunately, the black pastor is revered and greatly respected, sometimes past the point of doubt or critique. Take the three most popular black preachers of the 20th century. Over his lifetime the pastor Sweet Daddy Grace owned 42 mansions, and he only wore the best of clothes and traveled in the nicest of cars. Meanwhile his congregants, of the United House of Prayer, were largely poor southerners who faithfully tithed their 10% every Sunday. He advocated for one-man leadership, crowning himself as the sole trustee of the church’s finances. He flipped the funds to fund his lavish lifestyle. In the present day, House of Prayer has 30-50,000 congregants. Sweet Daddy Grace’s two contemporary rivals were similar swindlers.

Prophet Jones of Detroit was presented with lavish gifts and piles of money from his congregants every year for his birthday. The eight-day celebration was deemed a holiday and replaced Christmas. He was the same man who fancied himself “God’s sole representative on Earth”, even going as far to claim healing powers and psychic abilities. His followers were also a majority of poorly educated southern blacks, who had migrated to Detroit. To make matters worse, it wasn’t his thievery that brought about his downfall. It was the revelation that he was a homosexual. Father Divine of New York, who preached zero tolerance abstinence, used land and property owned by his flock to keep up his lifestyle. He regularly took money from his followers, even once getting sued by one of them. He claimed to be divine, Jesus Christ reborn. Despite promoting anti-lynching legislation, Father Divine believed and preached that blacks perpetuate their own oppression by thinking racially.

Money has been a driving factor for many evangelical churches in this country, and not just the black ones- word to Jim Bakker. But it is not always money that brings out the bad in black churches. Here in the 21st century, scandals of prominent black preachers remind us how powerful these men are in the community— and how much they can get away with if they operate unchecked. Scandals like infidelity, tax evasion, embezzlement, and child abuse. Eddie Lee Long, the late senior pastor of New Birth Missionary Church, regularly denounced homosexuals, while also benefitting from Bush’s faith based initiative. So virulent was his homophobia that when four male former members risked public shame to accuse him of sexual abuse, his congregation barely blinked an eye. Long denied all accusations and settled out of court. This brings me to the ugly.

The Ugly

The black church is rigid with homophobia and hypocrisy. At my church there was a trans woman that everybody claimed to be praying for but nobody actually talked to. She was one of the first transwomen I ever encountered, with three inch acrylic talons elaborately painted and ruthlessly maintained. When the pastor opined about deviance, heads would slightly turn towards single mothers or the transsexual woman, if she happened to be in church that day. I remember hearing adults talk shit about her in the church parking lot, but it barely registered to me back then. She was just an other. She was one of the people who stuck out, like girls rocking blue jeans instead of Sunday dresses. “She should be ashamed of herself, dressing like she’s running errands,” one of my least favorite aunts would say over a cigarette, narrowing her eyes at some unfortunate victim who probably had nothing else to wear to service that morning. Even though the preacher would say “come as you are”, my church was the kind of place where you came to impress. Who could wear the best outfit? Who was seen tipping the most cash in the collection plate? Who screamed amen the loudest? Who was willing to jump up from their seat and run, shoeless, up to the front of the church every Sunday, screaming thank you? It was all so theatric. It didn’t seem real. And yet, so much of what the church influenced was very real. I’ve not only read the studies in academic journals that state many black churches condemn homosexuals, but I’ve been there to receive those messages myself. Those messages are why I sat up at night for hours as a child, praying to God to make me straight and normal.

Studies have shown that among black men, “regular church attendance was significantly associated with more homophobic attitudes towards gay males.” This stems from a long pattern of respectability politics, pushed by the black church in the face of American racism. As noted by Angelique Harris, “Post-slavery, to distance itself from [the] negative portrayal of black sexuality, the black community embraced a very conservative stance towards sex and deviant sexuality, such as pre-marital sex, extramarital affairs, out of wedlock births, and especially homosexuality.” Respectability is a key aspect of the black church’s existence, and has unfortunately created a culture of intolerance for the community. Bayard Rustin, a key organizer of the civil rights movement and Martin Luther King’s close friend, was shunned from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference when revelations about his sexuality were made. Untold numbers of Bayard Rustins were held back from their full potential to make others comfortable. This culture contributed to the social hierarchy that has given so much power to pastors, while also increasing homophobia and sexual double lives among church members. Y’all know what I’m talking about. Sermons and whispers about faggots, sissies, deviants, and homos keep gay congregants in the closet, but they’re the ones who often organize the dance recitals and dominate the choirs. In a 2010 study reaffirmed by findings in 1997, it was found that congregants often know about the sexual orientation of their “choir directors, lead singers, ushers, organists, deacons, and even pastors,” but it is rarely discussed openly. But not talking about homosexuality in church (apart from quoting Leviticus) has led to a neglect of the AIDS crisis in the black community.

The initial 1981 report about HIV listed five homosexual men to be infected, all rightfully assumed to be white. The report didn’t mention the two black men- one a gay American and the other a straight Haitian- also infected with the virus. Like most of the country in the 1980s, the black community believed that AIDS was reserved for homosexuals. Even more specifically, most believed AIDS was for white homosexuals. While whispers about gay church members had already existed, the AIDS crisis intensified things. This happened when “prominent young male members within black churches began to die mysteriously of ‘cancer’ in the mid-80s and early 90s.” But it was the infection of basketball player Magic Johnson that sent a shockwave through the community. This forced some churches to acknowledge AIDS among black women (who were rapidly being affected), but in the present, many still don’t like to talk about the virus, thanks to its stigma as the “gay disease”. This is particularly true for more conservative southern denominations.

This is literally killing us. According to a recent article in the New York Times, “the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention… predicted that if current rates continue, one in two African-American gay and bisexual men will be infected with the virus.” HIV rates are skyrocketing in southern states, where poverty, religiosity, lack of education, and stigma converge to leave people in the dark. Per the same article, “The South also has the highest numbers of people living with H.I.V. who don’t know they have been infected, which means they are not engaged in lifesaving treatment and care — and are at risk of infecting others.” This holds true despite the initiation of the Affordable Care Act, which increased the number of people aware that they were living with HIV. The ACA played a big part in easing the HIV crisis that had worsened during the Bush Administration, when little attention was paid to the virus in black-American communities. Instead, tax dollars were sent overseas to help nations in Africa. According to Greg Millett, senior policy adviser for the Obama administration’s White House Office of National AIDS Policy, “The White House said H.I.V. is only a problem in sub-Saharan Africa, and that message filtered down to the public. Though the Bush administration did wonderful work in combating H.I.V. globally, the havoc that it wreaked on the domestic epidemic has been long-lasting.”

Why does this matter to whoever is reading this? Two words: Donald Trump. “The key to ending the AIDS epidemic requires people to have either therapeutic or preventive treatments, so repealing the A.C.A. means that any momentum we have is dead on arrival,” said Phill Wilson, chief executive and president of the Black AIDS Institute. With the repeal of Obamacare looming over the country, black churches have a duty to increase AIDS awareness or we will be stepping back in time. HIV is not just for homosexuals, and the sooner black churches and their congregations detach the sin from the virus, the more lives will be saved. Early 21st century efforts to attack the AIDS crisis in the black community were largely successful for women, but not for gay and bisexual men. “Between 2005 and 2014, new H.I.V. diagnoses among African-American women plummeted 42 percent, though the number of new infections remains unconscionably high — 16 times as high as that of white women. During the same time period, the number of new H.I.V. cases among young African-American gay and bisexual men surged by 87 percent.”

Every time I listen to someone harp on about HIV being a punishment from God or a conspiracy of the government to kill black people, I tremble from the weight of the excuses. No matter what you believe, black men and women have the highest rates of HIV among all races and help won’t be coming from the government. As reported by the New York Times, “Despite the higher H.I.V. diagnosis and death rates in the Deep South, the region received $100 less in federal funding per person living with H.I.V. than the United States over all in 2015.” It was also mentioned that America would need to invest 2.5 billion to fully attack the AIDS crisis among black men, a cruel number for a country in the middle of slashing budgets left and right. With all of the power black churches have, they must all step up.

Strung Out

Karl Marx is often quoted as writing “religion is the opium of the masses”, but this is a misquoted fragment that lacks context.

Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.

Marx was saying that religion serves a practical function to those suffering in the world, but it also makes them docile and complicit in their suffering. To me, Marx was right to compare drugs to religion. When times get tough, some people turn to alcohol, sex, or drugs. Others turn to Jesus. Like drugs, religion alleviates pain and can provide fond memories. In the black community, religion has been a pleasurable way to escape the hardships of racism and poverty. This pleasure manifested itself in the black church. The music, the food, the dancing, the celebrations. Also like drugs, religion isn’t just for pleasure. It has a practical function. It brings people together for greater purposes and can give life meaning. The black church, a legacy of the black Christian religion, has served as a safe haven and community resource, whether you believe Jesus Christ to be your savior or not. Black culture is so infused with the black church that it is impossible to talk about one and not the other. Though the church is not my safe haven, it is one to millions of my brothers and sisters. I used to be interested in challenging people’s belief in the Christian God, calling it a white supremacist drug for the black masses, but I realized that the “drug” is quite necessary to our progression. If I (an atheist) can admit this, then surely believers can admit that Christianity —and by extension black churches—teeters on the line between useful medicine and dangerous poison. The pleasant effects can camouflage very real issues like homophobia, sexual abuse, and financial exploitation. The pleasant effects run a risk of making us complicit in our own suffering. Please don’t be too high to see that.

References

The Rise and Fall of Detroit’s Prophet Jones (Richard Bak)

A People’s History of the United States (Howard Zinn)

America’s Hidden HIV Epidemic (Linda Villarosa)

“Hating the Sin But Not the Sinner”: A Study About Heterosexism and Religious Experiences Among Black Men (Pamela Valera and Tonya Taylor)

Sex, Stigma, and the Holy Ghost: The Black Church and The Construction of AIDS in New York City

Homophobia, Hypermasculinity, and the US Black Church (Elijah G. Ward)

A Religious Portrait of African-Americans

Melissa Gray

June 13, 2017 6:06 am

Wow. Very thought provoking and valid points. I often had thoughts and I alway have had a moral delima when it comes to church. This is a powerful perspective! Thank you for sharing.

Kayla Harvey

June 16, 2018 3:33 am

Loved this essay. Addresses a great set of topics that the older generation is much more oblivious to within the church.