This is an essay from my upcoming book, Angry Black Girl. I was inspired to release it early after reading about the assault of a sixth grader in Michigan who refused to stand for the pledge.

This is an essay from my upcoming book, Angry Black Girl. I was inspired to release it early after reading about the assault of a sixth grader in Michigan who refused to stand for the pledge.

I don’t recall the exact moment that I began questioning the pledge but it was fifth grade when I started refusing to put my hand over my heart and recite those loaded words. The phrase “I pledge allegiance” felt sticky and wrong in my mouth. At first, I stopped saying the words. Then, I stopped standing up altogether. My fifth grade teacher, a stern middle aged blonde who often showed contempt towards me, did not approve. She pulled me aside before recess and demanded that I say the pledge of allegiance, or that she would be forced to call my mother. She did not ask me why I refused to say the pledge. She just wanted to make sure that I said it. She, like many, assumed that a ten-year-old should pledge her unwavering loyalty to a country while knowing very little about it.

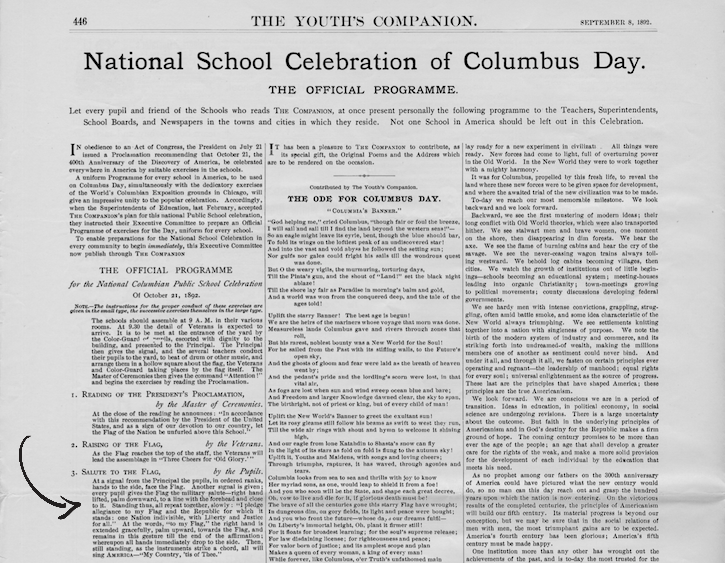

The American Pledge of Allegiance has been around in various forms since 1892, when Colonel George Balch yearned to teach American loyalty to children. He was especially keen on kick starting American nationalism in the children of immigrants. His original words were ‘we give our heads and hearts to God and our country; one country, one language, one flag!’ Five years after Balch, Francis Bellamy tweaked the pledge for a special edition issue of the popular children’s magazine The Youth’s Companion. The pledge was going to be used to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival. The official words were now ‘I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.’ It was accompanied by the Bellamy Salute, the same gesture adopted by Nazi Germany decades later. Bellamy had considered including the word “equality” in the pledge, but he knew that opponents of blacks, indigenous people, and women wouldn’t want to recite those words.

The American flag was commercialized for public schools at the same time, and the flag observing ceremony was pushed by Bellamy and the National Education Association. In June 1892, they succeeded in persuading President Benjamin Harrison into making the pledge, salute, and flag the center of Columbus Day. On October 12, 1892, students across the nation pledged their loyalty to America for the first time. Many schools eventually made the pledge a required part of the school day.

In June 1942, during the turbulence of World War II, the pledge was officially adopted by congress. This was the same year that roughly 70,000 Japanese-Americans were rounded up and tossed into internment camps. The pledge, which called for liberty and justice for all, reeked of hypocrisy. In the ten years prior, a quiet war had been brewing between Jehovah’s Witnesses and advocates of the pledge. In Nazi Germany, thousands of Jehovah’s Witnesses were arrested for not saluting the swastika stamped flag. To show solidarity, some American Jehovah’s Witnesses instructed their children to abandon America’s pledge. The responses weren’t pleasant. Students were suspended or expelled and threatened with reform school. Parents were arrested. Some Jehovah’s Witnesses even experienced violence.

In 1940 the Supreme Court ruled that public school students could be compelled to say the pledge, no matter their religion. Not saying the pledge was considered an act of insubordination. This was overturned in 1943’s West Virginia State Board of Education vs Barnette. The Supreme Court found that the free speech clause in the 1st amendment protected students from being forced to salute the flag or say the pledge. Today, saying the pledge of allegiance is optional, but students still get harassed for not saying it. For instance, it was just reported that a Michigan sixth grader was “violently snatched out of his chair and made to stand” after exercising his right to free speech. On a separate occasion, he was yelled at.

My fifth grade teacher was disgusted when I stopped saying the pledge. She thought I was making trouble. After all, it was only three years after 9/11 and American nationalism was at a fever pitch. There is a lot of confusing language used to describe that era. If you ask the wrong person, they’ll call that era patriotic. But George Orwell defined patriotism as “devotion to a particular place and a particular way of life, which one believes to be the best in the world but has no wish to force on other people.” On the flip side, he described nationalism as feeling your way of life or country is superior to others, and should be adopted by everyone. In the months and years after the 9/11 attacks, sales of flags increased but so did the feelings of xenophobia and nationalism. Americans oozed love for country and grew fervently opposed to those they saw as “other”. Attacks on Middle Eastern and Muslim Americans increased to never before seen levels. The violent criminals who attacked them were publicly shamed, but then heralded as heroes and patriots on right wing blogs and forums. It was this twisted nationalism that fueled the average citizen’s belief that we should incite war in the Middle East. Additionally, there are essays and entire books that can be written about the link between post-9/11 American nationalism and the presidential election of Donald Trump.

Despite my teacher’s warning, I continued to not stand for the pledge. She followed through with her threat to call my mother, and I’m sure that she was thoroughly surprised when my mother stood behind my decision. I can only imagine what kind of rebuke she handed down to my dear teacher, who after that call never asked me to stand for the pledge again. For the rest of the year she always addressed me with the utmost respect, albeit her eyes were always two or three inches above my head, as if she was afraid to look me in the eye. What my teacher didn’t grasp was that when she rebuked my decision she was denying me access to liberty and justice, a core component of the pledge she was so desperate for me to say. Even with my naive understanding of the world at the age of ten, I knew she was wrong. Thirteen years later, I can articulate that America is also wrong for dipping children into blind allegiance before they ever have the inclination to question it. There is a danger in making American kids think that this country does a thorough job at extending liberty and justice to all of its citizens, no matter their race, religion, gender, or socio-economic status.

The concept of the pledge would be less terrifying if it wasn’t such blatant propaganda. The words of the pledge are absorbed in kindergarten when the mind is young and malleable. As your vocabulary expands, the words become more familiar. As the years go by, the assurances of justice and liberty for all are validated by shallow American history lessons that skip past genocide, the most brutal aspects of chattel slavery, mass sterilization, and systematic oppression. Set adrift on manipulated memory bliss of American atrocities, the pledge becomes righteous and sacred. The flag, truly a symbol of imperialism, theft, genocide, and injustice- becomes more important than the things its supposed to represent. You know, like justice, liberty, and equality for all. Have you ever noticed that conservatives and liberals alike get angrier about a burning flag than police brutality, housing discrimination, or other components of white supremacy? These are the same people who see valid critiques of America’s racial issues as blasphemous or blown out of proportion. They are essentially rendered incapable of revolution. They have no desire to revise this country’s race relations or balance it’s economic inequalities. Why? They are brainwashed into unyielding support of a country that has sanitized its past for generations of school children.

Kiara Nicole

June 26, 2018 9:17 pm

I stumbled across you via twitter because your thread had gone viral. This essay, your words and your work all resonate with me so deeply. I can’t wait to purchase your book.