From Abolition Papers to BET, How Have Black People Spread the News?

In today’s digital world, black people can get their news from anywhere. Plenty of topics that were never covered in black media just a century ago, from environmental racism to black nationalism to sex, are available with just the click of a button. This is the benefit of the glorious internet, where fact-checking journalists can exhaustively labor over groundbreaking pieces that get less views than a post about the latest Kardashian shenanigans or new movie gossip.While many of us notice the lapse in news coverage (or tremendous bias) when it comes to mainstream outlets handling our stories, we have also noticed a death of black-owned media outlets that put our experiences and narratives first. Black-owned radio stations have dwindled since 1996 thanks to the Telecommunications Act, which allowed radio conglomerates to take over in local areas and ignore the needs of area citizens. Out of over 1,000 tv stations in the country, black people own a paltry nine. The major black magazines still left are struggling to stay afloat, with historic publications like Ebony routinely facing accusations of not paying writers. Essence Magazine just wrestled itself from thirteen years of Time Inc ownership this year to be black owned. Viacom owns Black Entertainment Television. Several of the most popular black blogs have been picked up by larger companies, whose advertising dollars cease to appear if certain topics are breached. In our increasingly damaged and racially divided country, this spells trouble for black citizens. Even before our emancipation from slavery, the ability to tell our own stories and criticize the America we live in has been crucial to our survival and progression. Without our own media outlets, we are placing our stories and our futures into the hands of the oppressors.

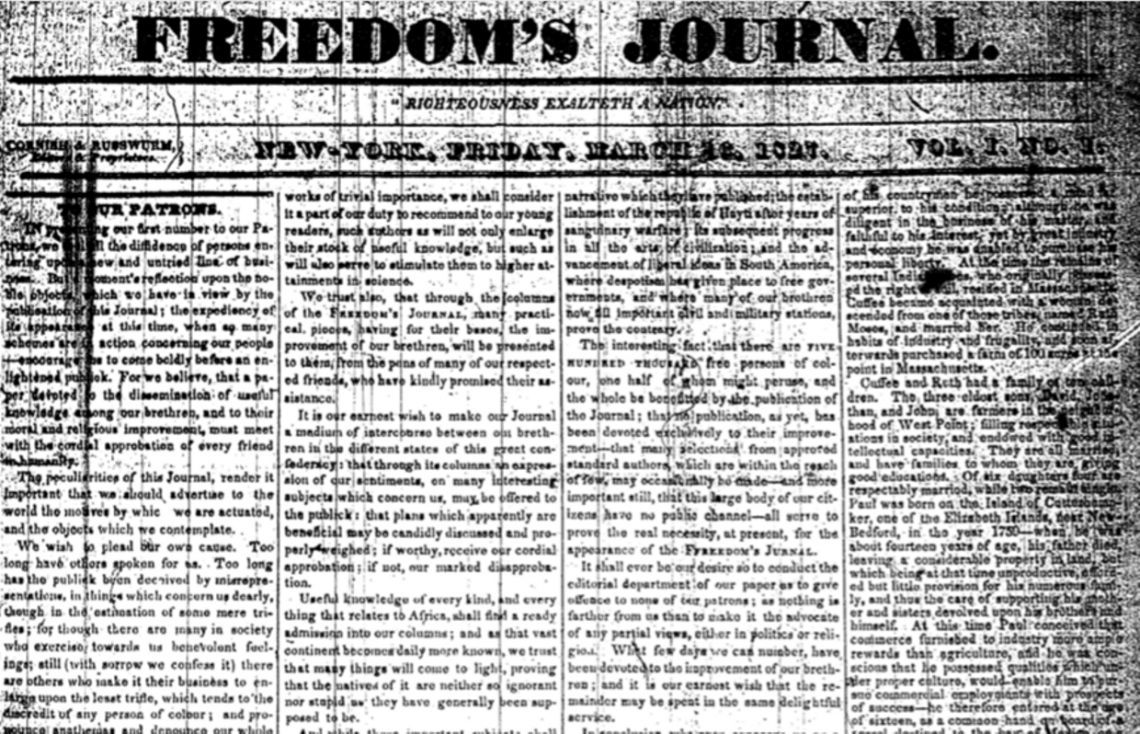

Before the Civil War, the two pieces of media that gave slaves and free blacks leverage in the fight for abolition were slave narratives and abolitionist newspapers. These two things offered an alternative and raw view of slavery that couldn’t be ignored by the masses. It was one thing for white people to hear abolitionists of their own hue describe the horrors of slavery that they had never experienced first-hand, and completely another to hear it straight from the source. The very first black-owned newspaper was called Freedom’s Journal, published in Winter 1827 by three black New Yorkers who stated, “Too long have others spoken for us.” The paper shut down after just two years, but by the Civil War 24 other black papers had been established, the most notable being Frederick Douglass’s The North Star (1847). He wrote, “[It is] essential that there should arrive in our ranks authors and editors as well as orators, for it is in these capacities that the most permanent good can be rendered to our cause.” In the months and years following the end of the Civil War, there was an explosion of over 500 black newspapers, mainly printed on church presses.

Reconstruction was an era of white fear, marred by Ku Klux Klan violence and confederate veteran retaliation that culminated in lynchings and rapes. These events went unreported in white papers, or were told in sympathetic tones. So black newspapers took on the duty of reporting these cases, though in the South this could mean facing murder and destruction. One famous example is that of Ida B Wells, who reported on the lynch murders of her three friends in the Memphis Free Speech in 1892. The white editor of the local Memphis Commercial urged for retaliation against the “black wench” and the newspaper office was burnt to the ground. No copies of the Memphis Free Speech exist today, and we only know of its reporting through re-printed articles in other papers. Despite the risks of running a black paper, entrepreneurs and journalists forged on. The Afro-American Press Association was founded in 1890. By 1910 the number of black owned papers had settled to a still respectable 275. Two of the most iconic were the California Eagle and The Chicago Defender. Both played integral roles to the Great Migration of black people out of the Jim Crow South. The California Eagle was founded by John J Neymour in 1879, who wanted to offer advice and information on moving to California by listing jobs and housing. It was made an institution of the early 20th century by Charlotta Spears Bass, who made a deathbed promise to Neymour in 1912 to be the editor of the paper. She would do so for forty years, proving to be the right choice by growing the papers circulation and even leading a campaign against 1916’s racist film, Birth of a Nation.

The Chicago Defender was founded in 1905 by Robert S. Abbott, who originally tried being a professional printer and lawyer (he even graduated from law school) but couldn’t get into either field due to discrimination. Luckily for Black America, he entered journalism. There are a number of things Abbott did with the Defender that led to him being the first black millionaire publisher. For starters, he employed tactics of white papers, like sensationalizing stories with bold headlines and sarcastic commentary. Black people were referred to not as negroes, but as “The Race.” Also, because he was based in Chicago, Abbott could say things that southern black papers couldn’t, and made sure to cover every lynching. He sent copies of The Chicago Defender down south, where he urged black people to stand their ground, fight back, and kill white folks if need be. “When the white fiends come to the door, shoot them down. When the mob comes, take at least one with you,” historian James Grossman repeated from the Defender. The paper became a popular read in black gathering places, and readers were encouraged to share the papers with as many friends and family as possible. After the northern labor shortage during World War I, Abbott began instructing black people to move north for jobs and opportunities. He started publishing job listings, one-way train schedules, housing information, and detailed descriptions of black Chicago neighborhood amenities to entice black southerners into moving. “Every black man for the sake of his wife and daughters especially should leave even at financial sacrifice,” wrote one editorial. White southerners even started noticing the migration and got so pissed that a crucial (and underpaid) component of the workforce was leaving that they began trying to confiscate The Chicago Defender. Even though the paper pushed respectability politics (namely publishing pieces cautioning black southerners from bringing their ghetto ways up North), it helped change the landscape of black America in the 20th century. That’s clout.

There was a surge of black newspapers after 1919’s Red Summer, a time in which hundreds of black people were murdered and dozens of violent riots took place. Racial tension and a labor shortage among freshly-returned World War I veterans and newly-transplanted black southerners in Northern cities were at the root of all the bloodshed. More than ever black papers served the important role of reporting on lynching and informing readers on the best ways to navigate racism in unfamiliar cities. These papers became an absolute staple of the black community for the next 40 years. The pros were that they could print what they wanted and report on things the white press ignored. The advancement of photograph technology meant more positive images of black life that weren’t white drawn caricatures or stereotypes or photos of lynching victims. There were even black cartoons that contrasted the racist imagery in white papers. Black writers at these publications were treated like celebrities in the community and held in high regard. Meanwhile, they were painfully underpaid, due to the major con of black newspaper ownership: a lack of advertising dollars. Black papers depended on circulation for money, while white papers could depend on companies desperate for ad space to target white consumers. Black papers had to take what they could get, and it’s no surprise that papers from these time periods are peppered liberally with skin bleaching advertisements.

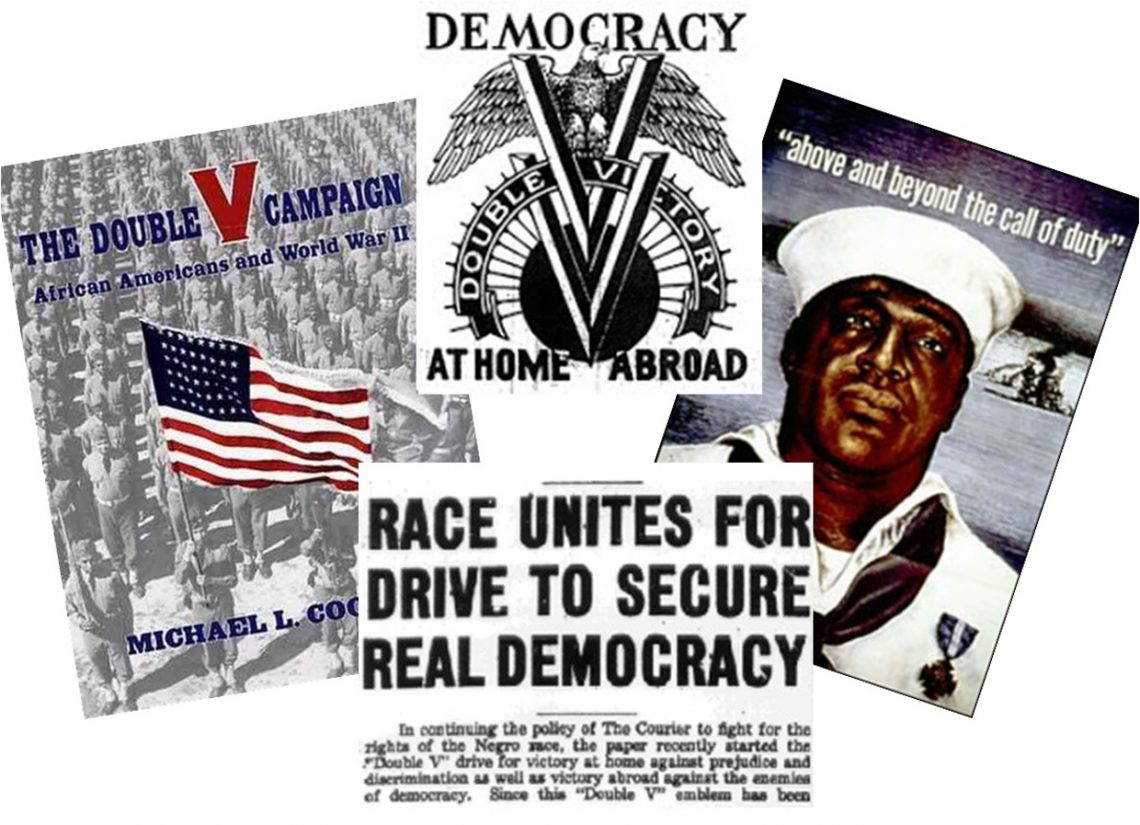

The other big paper during the first half of the twentieth century was The Pittsburgh Courier (1907-1966). It initially ran weekly by a group of five men, but came under Robert Lee Vann in 1910 and saw major growth after World War I. The Pittsburgh Courier is noteworthy because it allowed for conflicting beliefs within its pages, with 15 columnists at its height, who ranged from radical to conservative. The Pittsburgh Courier demonstrated it’s influence over the black population when Vann encouraged black people (who usually supported Republican candidates if they could vote) to vote for the democratic Roosevelt in the wake of the Great Depression. He was rewarded with the empty gift of being Special Assistant to the Attorney General. I say empty because he quit after two years of largely being ignored in the position due to his skin color. The Pittsburgh Courier came under fire during World War II when it advocated for fighting both the war overseas and fighting racial discrimination at home. It became known as the “Double V” campaign (read: Double Victory), and even spawned a hairstyle, a song, fashion, and baseball events. It wasn’t long before this campaign spread to other papers. The Pittsburgh Courier and other papers also reported on racism in the military, which the government thought would hurt morale. It’s no surprise that the military began trying to keep troops from receiving black newspapers, even going so far as to burn them.

J. Edgar Hoover considered the Double V campaign seditious, claiming that it would incite rioting and terrorism, so he convinced Roosevelt to order hearings to prove it. In 1942 Hoover presented reports to Attorney General Francis Biddle, and asked him to indict a group of black publishers for treason. The new publisher of The Chicago Defender, John Sengstacke, met with Biddle in 1942. Biddle informed him that “If you don’t stop writing this stuff, we’re gonna take some black publishers to court under the Espionage Act.” Sengstacke was unfazed. “What are we supposed to do about it? These are facts and we ain’t gonna stop. That’s what it’s all about.” Amazingly, Sengstacke and Biddle reached an agreement that nobody would be prosecuted if the campaign didn’t escalate.

By the end of the war, black news circulation was a combined 2 million. But there was another new player on the black media field: Johnson Publishing and Negro Digest, the first truly popular black magazine. Magazines up until that point had never been a popular medium. Prior to the 20th century, there were church and abolition “magazines” that would bore the average reader to tears. Then there was Colored American Magazine, which debuted in 1900. For its first four years, leading contributor Pauline E Hopkins critiqued Jim Crow America, something that led to her firing when the notoriously racist-accommodating Booker T. Washington acquired the magazine in 1904. Just two years later the magazine asserted that it was not focused on activism or “difficult and complicated social problems.” By 1909 the paper was over, prompting W.E.B. Dubois to write in NAACP’s own magazine, The Crisis, that it had become so “conciliatory, innocuous, [and] uninteresting that it died a peaceful death almost unnoticed by the public.” There was also the single magazine issue of Fire!!, published in 1926 by various members of the Harlem Renaissance. Leaders of the Talented Tenth found it vulgar and regressive for addressing colorism, homosexuality, promiscuity, and sex work. The irony? After the single issue, Fire!! Headquarters burned to the ground and never reopened.

While there were plenty of black newspapers during the ’40s, John H. Johnson saw a void to be filled in magazines. Johnson started The Negro Digest with a tiny $500 loan, as both black and white people he knew rejected investing because they thought a black magazine would fail. After building success with The Negro Digest, Johnson published Ebony Magazine in 1945, targeting middle-class blacks with glossy articles, moderate politics, and photos of black life. Because the articles weren’t too radical, advertisement companies felt comfortable sending custom ads. Jet Magazine followed in 1951, which addressed racism and the civil rights movement along with current news, but was also moderate and glossy by featuring articles on fashion, gossip, scandals, and celebrity more than “radical” papers and introspective magazines like Negro Digest (which was later rebranded as Black World in 1970 with an Afrocentric vibe). At the same time that Johnson was running his publishing empire, scandal “true story” magazines like Jive were being manufactured by white-owned companies targeting black consumers. These magazines included sexy women and trifling stories that served as a sharp opposition to the carefully curated image of respectability in Ebony and Jet. Still, Johnson publishing faced little competition from actual black-owned magazines well into the 70s.

Black newspapers, along with Ebony and Jet, continued to be pillars of the black community during the Civil Rights Movement. Jet and The Chicago Defender published the brutal and sobering images of Emmett Till’s corpse. The California Eagle published passionate editorials on discriminatory housing and police brutality, angering cops, the real estate association, and the housing authority. The FBI began following the editor, Charlotta Bass, and the post office even launched an investigation to revoke the paper’s mailing privileges on the basis that Bass was a communist. This was a big no-no during the period of the red scare. Her “radical” stance of connecting capitalism and racism made her a troublemaker in the eyes of many blacks, and circulation for The California Eagle dwindled. Subscribers began turning to the fluffier Los Angeles Sentinel, so Bass ended up selling the paper in 1951. It would shut down just 13 years later.

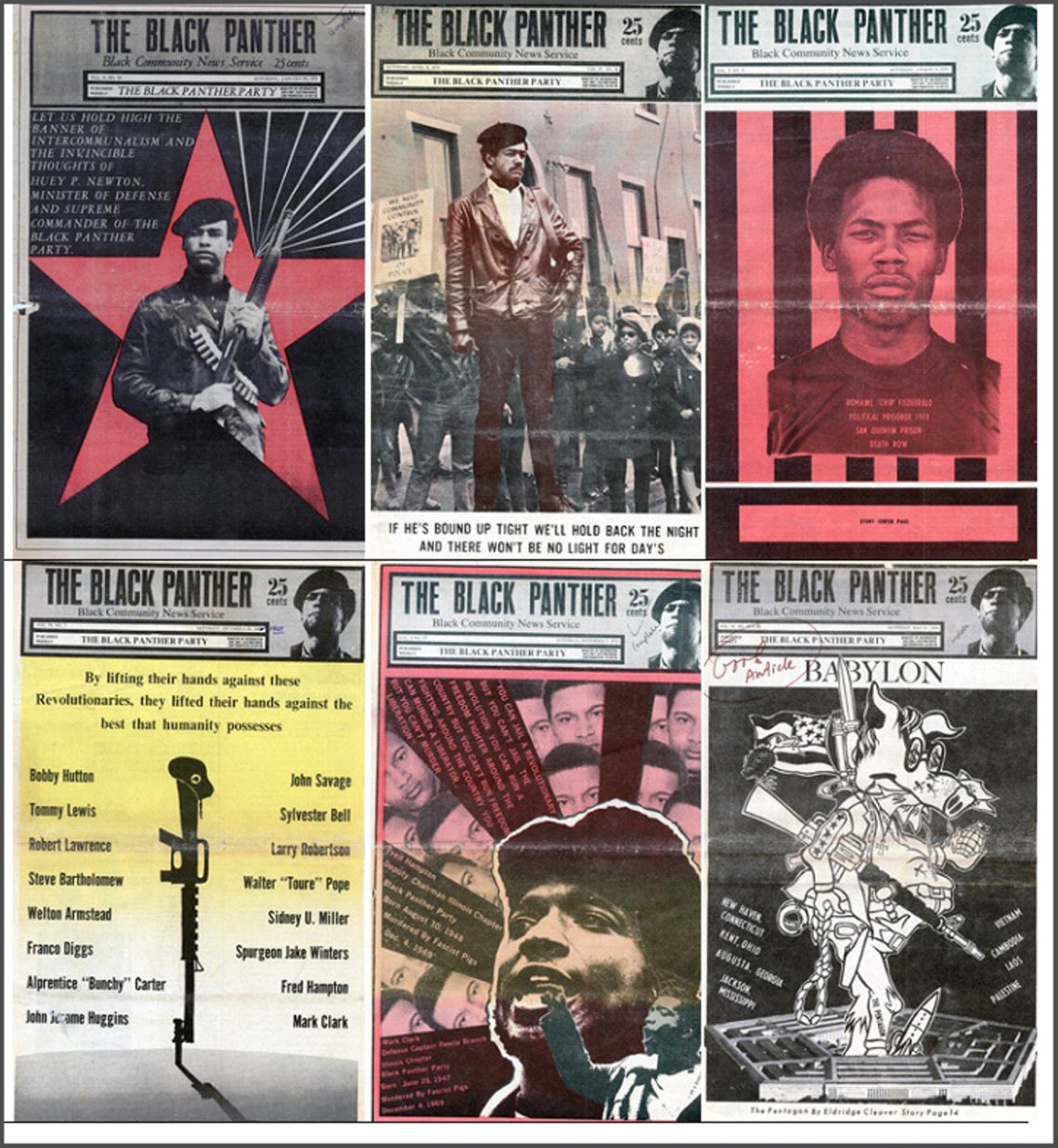

While many black papers at this time avoided discussing class issues or criticizing capitalism, many tried to cover the ongoing civil rights-related violence of the south with the little resources they had. But increasingly in the 50s and 60s, they were competing with white media, who were now covering the movement in print and on TV. Suddenly, black people could read about themselves in mainstream papers. These same papers were increasingly hiring black writers, and for much better pay than what was offered at black papers. Compounded with the impact of TV and radio on print media, black papers began struggling more than ever before. Those who managed to survive were now hooking major advertisement deals from companies who suddenly saw the revenue potential in the black community. While this meant black papers could now depend on ad space rather than circulation for funds, they now faced a decreased amount of editorial control. Papers found themselves toning down criticisms of white America, which would only add to the alleged post-racial narrative that began to dominate our society in the 70s. The exceptions could be found in radical newspapers like the one printed by The Black Panther Party, which sold roughly 100,000-300,000 copies a week between 1968 to 1972. The Black Panther was the most popular black paper during those years, going for just a quarter a pop. Apart from this revolutionary and radical paper, by the end of the 60s, the influence and circulation of black newspapers had declined significantly, and would never again be as popular as they were in the early 20th century.

The slow death of newspapers didn’t mean the death of magazines. Ebony and Jet became more popular during the 70s and 80s, and the additions of publications like Black Enterprise (1970-), Essence (1970-) Right On! (1972-2011), Sister 2 Sister (1988-2014), and Emerge Magazine (1989-2000) meant more diverse selections for black consumers. However, the next great frontier of black media to be explored was TV. But the job that black print media did during the 20th century- informing, uplifting, and promoting discourse- would be abandoned in the TV world for quick bucks.

When future billionaire Robert L. Johnson launched Black Entertainment Television in 1980, it initially ran two hours of weekly programming in a few east coast cities. By 1984 it was 24-hours, most of the programming actually infomercials. By 1995 it reached 47 million homes. Johnson was tasked with generating programs for a broad spectrum of black people. A major chunk of programming was music videos and music specials, filling a need for broadcasting black artistry that MTV wasn’t interested in. In 1988 BET News with Ed Gordon was added, kicking off a short-lived trend of regular news programs on the channel. BET’s most notorious news special of the 90s was an interview with the recently acquitted OJ Simpson in 1995. But by 1996, the channel was under fire for its lack of original programming and news. BET News was a weekly show, and there were two daily 60-second news briefs. Wrote Holly Bass in March 1996, “BET’s programming covers three basic groups: music, infomercials, and other. The “other” category is principally comprised of reruns- reruns of music award shows, reruns of sitcoms, reruns of reruns.” Commentary like this prompted Johnson to say, “When they’re on white networks they’re called classics. When they’re on BET they’re called tired ol reruns.”

The lack of original content was due to a lack of big advertisement money, and BET made the decision to supplement their lineup with comedy specials, which they found cheaper to produce than news and music videos. The most popular was Comic View, which aired 11 hours a week and had steady audiences of 450K or more. The issue? Comedians who appeared on the show were overworked and paid $150 per appearance, with no residuals from all of the reruns. Once this became public knowledge, black entertainers finally spoke out against the channel. Said former Comic View host D.L. Hughley, “Because it’s black people mistreating black people, everyone’s been hesitant to speak up.” Johnson, who was anti-union, was pissed. In 1999, Aaron McGruder used his The Boondocks comic strip to criticize BET and Johnson, whom he saw would put dollars over the interests of black people. Johnson wrote a public letter saying, “The most appalling of McGruder’s reckless charges was that BET ‘does not serve the interest of black people.’ Our response to this slanderous assertion is that the 500-plus dedicated employees of BET do more in one day to serve the interest of African-Americans than this young man has done his entire life.” Popular series like BET Teen Summit (1989-2002), BET Talk with Tavis Smiley (1998-2002), and Lead Story (1995-2002) seemed to back this up. But just a little over one year later, Johnson sold BET to Viacom for 3 billion dollars and over 40 employees were fired. The notoriously raunchy BET Uncut began its five-year run in 2001. By 2002 all news programs had been eliminated except for BET Nightly News (2001-2005). BET had even come to own Emerge Magazine in 1991, which focused on political and social issues. It too was shut down in 2000. “An African-American company gains a considerable amount of capital when it sells out to a powerful conglomerate,” said former Lead Story panelist George E. Curry at the time. “But it also loses something important. Regardless of how BET tries to spin it, the loss of these important programs represents a major setback for the Black community.”

In the years that followed the Viacom purchase of BET, the channel has continued to live up to its name as “entertainment television” and little more. While it could focus on making history, current affairs, and social justice issues more entertaining to young black Americans, the channel prioritizes content that reinforces stereotypes from played 80s and 90s sitcoms, promotes celebrity idolatry, glorifies wealth and violence… and somehow ties it all together with Christian rhetoric and gospel on Sunday mornings. Where is the substance? Where can we turn for black news that matters? In an era where readership of black newspapers has fallen every year since 2009 and many magazines have stopped printing physical copies, the answers are clear. The internet. Gelled between hentai porn, viral cat videos, and nazi hate groups are glimmering pockets of hope for what could be the final frontier of black media. Sites like Blavity, The Grio, and The Chicago Defender, the latter of which is still reporting on black issues after 113 years. But we can’t expect these outlets to struggle, get big, and be acquired by wealthy corporations. We must discuss ways to build our media outlets up instead of selling them out.

These twitter accounts, blogs, and even patreon websites (wink, wink) are reporting on news that matters with limited funding- and this is bittersweet. The same way black newspapers of the early-20th century had great freedom in reporting thanks to having no advertisers to answer to, internet-age media outlets like mine can say what needs to be said. But like our 20th-century forerunners, there is a serious drawback. We don’t have the budgets to keep up with the outlets that churn out nonsense. We shouldn’t have to hope a serious black issue goes viral enough so that hit-obsessed outlets like TheShadeRoom pick it up and “report” on it. Where is our black CNN or MSNBC? The true battle of our digital world is that black media outlets must compete with glossy celebrity gossip for short attention spans. We must grapple with popular “for the culture” aesthetic sites that target black youth like The Fader and Complex, whose advertising budgets and clickbait headlines cheapen the culture to stay afloat. We must come across as party-poopers who do the nuanced legwork of addressing not just racism, but classism and wealth culture as well (something BET and other major gatekeepers don’t seem all that interested in). To truly be competitive with these internet outlets like TheShadeRoom and established behemoths like BET, we have to come up with creative ways to provide attention-grabbing visuals packed with substance– on a shoestring budget. We need to be making black scholarship more accessible to those in our community by packaging ideas and statistics creatively through black media.

Malcolm X once said, “If you’re not careful, the newspapers will have you hating the people who are being oppressed, and loving the people who are doing the oppressing.” TV and the internet caused many newspapers and magazines to fold, not just black ones. But our written media has always served a greater purpose than white media: to challenge racist views, to tell our own stories, and to inform each other about the race and class realities of America. The internet is our key written media now. If there is one thing to be learned from the history of Black American media, it is that we cannot rely on money from conglomerates or advertisement companies to honor the value of smart, nuanced, and insightful media in our community. If we don’t invest in black media and make it one of our top priorities, black people will continue to regurgitate the views of their oppressors.

What is your favorite black media website, twitter handle, or youtube channel? Comment below so other people (including me) can check them out!

References

- Bound For The Promised Land (Ethan Michaeli) 1/11/16

- Viacom’s BET Turns Into ET (George E. Curry) 12/10/02

- The Evolution of BET Network (Lisa Respers France) 6/10/10

- Pillars of Black Media, Once Vibrant, Now Fighting For Survival (Sydney Ember and Nicholas Fandos) 7/2/16

- The Black Press: Soldiers Without Swords (Full 1999 Documentary)

- Can The Black Press Stay Relevant (Bill Celis) 2/27/17

- BET Holdings, Inc. History

- Why B.E.T. Sucks (Holly Bass) 3/8/96

- The Colored Magazine in America (W.E.B. Dubois) 1912

- Chapter 11 of Forty Million Dollar Slaves: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Black Athlete (William C. Rhoden)

- A Brief History of The Colored American Magazine (Eurie Dahn and Brian Sweeney)

- Depressing in “The Promised Land”: The Chicago Defender Discourages Migration, 1929-1940 (Felicia G. Jones Ross and Joseph P. McKerns) 2004

- For 110 Years The Chicago Defender Has Made It’s Mark on History (Whet Moser) 1/14/16

- Propaganda and Aesthetics: The Literary Politics of African-American Magazines in the Twentieth Century (Abby Arthur Johnson, Ronald Maberry Johnson)

- Soul Babies: Black Popular Culture and the Post-soul Aesthetic (Mark Anthony Neal)