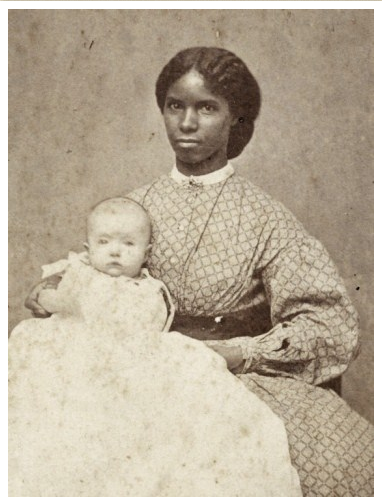

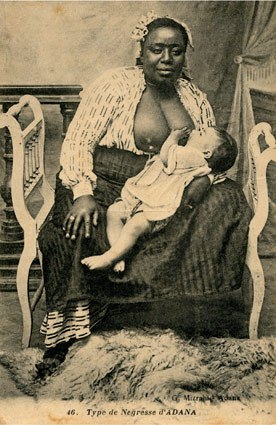

Before the mammy stereotype was born during the post-civil war revisionist period, every plantation had a mammy. As described by historian Kimberly Wallace Sanders, “more often [mammy] served as a generic name for slave women who served as a wet nurse or baby nurse for white children.” This was in large part to the trend of medical experts of the day discouraging mothers from breastfeeding. Outsourcing breastfeeding was not a new phenomenon during the pre-antebellum, as it had been occurring since the biblical times. Still, it is no less shocking that black women were good enough to give bodily fluids to white babies, but not good enough to be treated as human beings.

Before the mammy stereotype was born during the post-civil war revisionist period, every plantation had a mammy. As described by historian Kimberly Wallace Sanders, “more often [mammy] served as a generic name for slave women who served as a wet nurse or baby nurse for white children.” This was in large part to the trend of medical experts of the day discouraging mothers from breastfeeding. Outsourcing breastfeeding was not a new phenomenon during the pre-antebellum, as it had been occurring since the biblical times. Still, it is no less shocking that black women were good enough to give bodily fluids to white babies, but not good enough to be treated as human beings.

While black women were forced to give life to babies they did not birth, their own children sometimes went hungry. Per Sanders, “A lot of slave babies died during slavery because they weren’t breastfed. They were fed concoctions of dirty water and cows milk.” As any doctor will tell you, breastfeeding often creates a bond between the mother and child, and slave wet nurses were not immune to feeling affection for their white parasites, and vice versa. Said one European visitor to a plantation in the Carolinas: “Richard always grieves when Quasheen is whipped, because she suckled him.” Wet nursing did not end after slavery, and many southern white women continued to employ black wet nurses until the practice fell out of fashion in the twentieth century. Like their slave ancestors, “free” wet nurses were often kept from their children in addition to being forced to do other household chores, but with a severely unfair wage instead of no pay at all.

In the present, only 59% of black women breastfeed, compared to 79% of white women. Certified nurse and midwife Stephanie Devane-Johnson interviewed black women and found that some reject breast feeding because of the exploited wet nurses of slavery. I am left to wonder if the infrequency of breastfeeding among black women has to do with the high infant mortality rate in our community.

References

“If De Babies Cried”: Slave Motherhood in Antebellum Missouri

Distant Echoes of Slavery Affect Feeding Attitudes of Black Women

Minding the Children: Childcare in America From Colonial Times to The Present